High-level coding isn't always slower - the "what, not how" principle

This post is from the Software category.

Until the introduction of Rust, this rule of thumb for efficient code was usually true: if you want it to be as fast as possible, code it in C. It’s well-known that higher-level languages like Java, Python, and C# typically can’t catch up to the performance of well-designed C code, and there are many reasons for that, like the fact that C is almost always compiled ahead-of-time, while the others usually use some combination of precompiled bytecode, just-in-time compilation, and interpreters; or the fact that higher-level languages tend to use runtime memory management like garbage collection or refernce counting instead of statically-determined lifetimes.

Because of this efficiency distinction between higher-level languages and “C-level” coding, many developers get the impression that coding in a “higher-order logic” style instead of a step-by-step instruction style is inherently less efficient, regardless of the language. However, there’s compelling evidence that coding in a way that describes what you want to do and less about how to do it results in more efficient compiled code.

Compiler’s Intuition

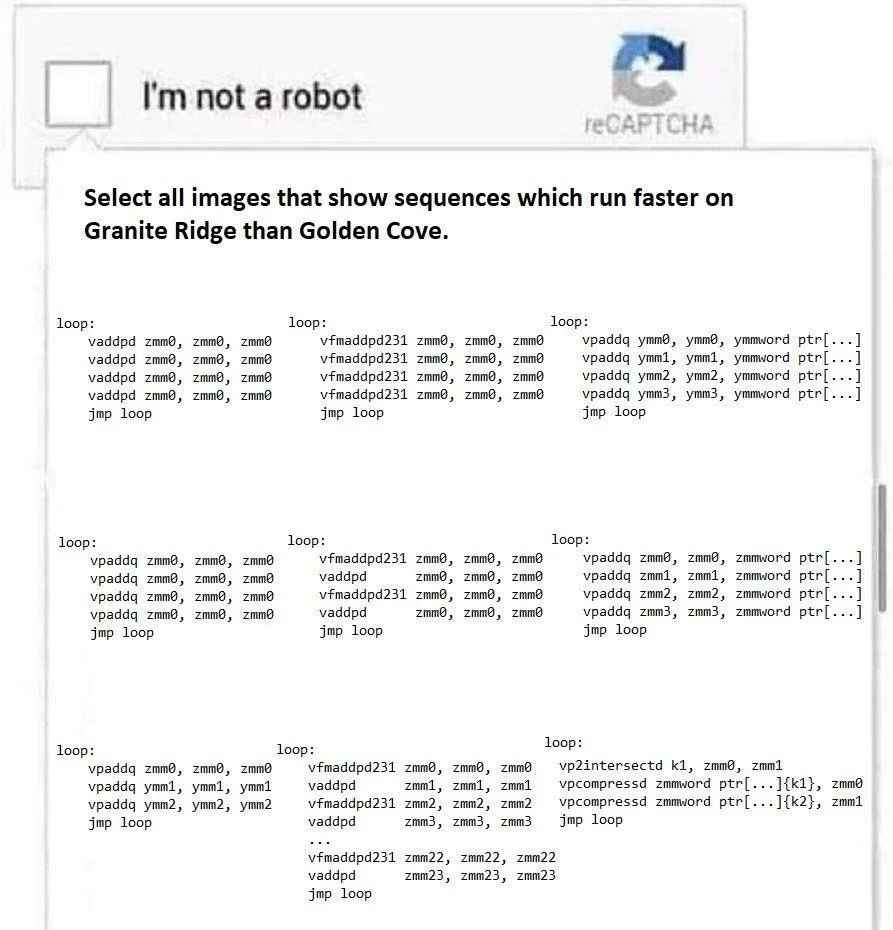

The prime directive of an optimizing compiler is this: Multiple source-code solutions that have the same behavior should result in the same machine code: the most efficient. Of course, compilers tend to fail at that, which is the whole reason for learning to write efficient code. But what if that’s less of a limitation of optimizers and more of a limitation of the paradigm.

Compiled languages aren’t just macros for assembly; modern compilers run code through multiple passes of optimization and try to find known patterns out of the hundreds of optimizer rules they’re equipped with. It’s all a complex pipeline to try to infer what your code is intended to do and transform it into a more efficient way to do it. But if it’s effectively going to replace your approach with its own, why design a specific approach to begin with?

Functional Programming: “What”, not “How”

The techniques of using higher-level standard library functions as the building blocks for code is quite common in functional programming languages like Haskell and Scala, as well as some multi-paradigm languages that try to be functional-programming-friendly, like Python. For interpreted languages, there’s only so much that can be done for efficiency, but a compiled language that follows this pattern would both be simpler for the programmer and leave plenty of leeway for the compiler to do its thing.

Compiler Knows Best

When you write code, do you plan for a specific chipset? Unless you’re doing embedded programming and are very familiar with the hardware, probably not. Do you look for ways to change your for loops that have simple math expressions inside into inline SIMD instructions? Unlikely. Did you know that, unlike most target architectures, where passing by reference tends to be faster, when targetting WebAssembly, it’s sometimes best to avoid passing pointers to stack-allocated values because it would require using a simulated in-memory stack that can’t be stored in CPU registers? Perhaps, if you’re an Emscripten contributor.

The good news is that you don’t need to, because compiler optimizations can do it for you. If your code is written in a way that makes it easy for the optimizer to infer what you’re trying to do and rearrange things as it sees fit, functionality is more of a consideration than efficiency.